Innovative service companies today recognize that they can supercharge

profits by acknowledging that different groups of customers vary widely in

their behavior, desires, and responsiveness to marketing. Federal Express

Corporation, for example, has revolutionized its marketing philosophy by

categorizing its business customers internally as the good, the bad, and the

ugly–based on their profitability. Rather than marketing to all customers in a

similar manner, the company now puts its efforts into the good, tries to move

the bad to the good, and discourages the ugly.(n1) Similarly, the customer

service center at First Union, the sixth-largest bank in the U.S., codes

customers by color squares on computer screens using a database technology

known as “Einstein.” Green customers are profitable and receive extra

customer service support while red customers lose money for the bank and are

not granted special privileges such as waivers for bounced checks. Providing

different service to customers depending on their profitability is becoming an

effective and profitable service strategy for firms like FedEx, U.S. West,

First Union, Hallmark, GE Capital, Bank of America, and The Limited.

These firms have discovered that they need not serve all customers

equally well–many customers are too costly to do business with and have little

potential to become profitable, even in the long term. While companies may want

to treat all customers with superior service, they find it is neither practical

nor profitable to meet (and certainly not to exceed) all customers’

expectations. Further–and probably more objectionable to quality zealots–in

most cases it is desirable for a firm to alienate or even “fire” at

least some of its customers. While quality advocates may be offended by the

notion of serving any customer in less than the best possible way, in many

situations both the company and its customers obtain better value.

Understanding the needs of customers at different levels of

profitability, and adjusting service based on those differences, is more

critical to the enterprise than has been previously held. Specifically, in

examining customers by profitability–and understanding the key elements of the

costs and revenues aspects of the profit equation–it is possible to actually

increase the current and future profitability of all customers in the firm’s

customer portfolio. The Customer Pyramid is a tool that enables the firm to

utilize differences in customer profitability to manage for increased customer

profitability. Firms can utilize this tool to strengthen the link between

service quality and profitability as well as determine optimal allocation of

scarce resources. Companies can develop customized products and services that

are more closely aligned with individual customer’s underlying utility

functions, thereby enabling the firm to capture more value from levels of

customers, resulting in higher overall customer profitability.

Beyond a General Relationship between Service Quality and Profitability

Prior to the 1990s, the general link between service quality and

profitability was still being questioned, but since the early 1990s, it has

been persuasively established.(n2) The evidence to support the linkage came

from a variety of sources and is now convincing enough to lead executives to

believe that a positive relationship does exist. The link was first established

through industry-wide, cross-industry, or cross-facility studies such as the

PIMS (Profit Impact of Market Strategy) project, which demonstrated a

correlation between quality and profits across both manufacturing companies and

service companies.(n3) In more recent studies, quality improvement and customer

satisfaction have been linked to stock price shifts, the market value of the

firm, and overall corporate performance.(n4)

Because firms are managed at the individual level and not the industry

level, executives still clamored for evidence that improved service quality

resulted in increased firm profitability. A growing number of studies bear this

out, showing that:

• service improvement efforts produce increased

levels of customer satisfaction at the process or attribute level,(n5)

• increased customer satisfaction at the process or

attribute level leads to increased overall customer satisfaction,(n6)

• higher overall service quality or customer

satisfaction leads to increased behavioral intentions, such as greater

repurchase intention,(n7)

• increased behavioral intentions lead to behavioral

impact, including repurchase or customer retention, positive word-of-mouth and

increased usage,(n8) and

• behavioral impact then leads to improved

profitability and other financial outcomes.(n9)

What is still missing in this research evidence is the recognition that

the link between service quality and profitability can be stronger if it is

recognized that some customers are more profitable than others. Service

investments across all customer groups will not yield similar returns and are

not equally advantageous to the firm. Different profitability segments are

likely to be sensitive to different service emphases and are likely to deserve

different levels of resources. As a small number of progressive companies have

discovered, they can become more profitable by acknowledging the difference in

profit potential among customer segments, then developing tailored approaches

to serving them.

The Limits of Traditional Segmentation

The idea of identifying homogenous groups of customers, assessing these

segments for size and responsiveness, and then more precisely creating

offerings and marketing mixes to satisfy them is not new. Traditional segmentation

is most effective when it leads to more precise targeting that results in

higher revenues or responsiveness to marketing programs. However, traditional

segmentation is not typically grounded in knowledge of the different

profitability of segments.

To build and improve upon traditional segmentation, businesses have been

trying to identify segments–or, more appropriately, profitability tiers of

customers–that differ in current and/or future profitability to a firm. This

approach goes beyond usage segmentation because it tracks costs and revenues

for groups of customers, thereby capturing their financial worth to companies.

After identifying profitability tiers, the firm offers products, services, and

service levels in line with the identified tiers. The approach has to date been

effectively used predominantly in financial services, retail firms, and

business-to-business firms because of both the amounts of data existing in

those firms and the ability to associate data with individual customers.

One example of an innovator in the field is Bank One, which recognized

that financial institutions were grossly overcharging their best customers to

subsidize others who were not paying their keep. Determined to grow its

top-profit customers, who were vulnerable because they were being under-served,

the Bank implemented a set of measures to focus resources on their most

productive use. The company used the data resulting from the measures to

identify the profit drivers in this top segment and stabilized their relationships

with key customers.(n10)

In another example, First Commerce Corporation knew that customer

segmentation could improve the effectiveness of all of its operations. After

dividing clients into mutually exclusive groups of individuals based on demographics,

the company then identified the reasons for profitability swings (including

balances, product mix, and transaction behavior). The firm then defined three

unique segments: the smart money segment, the small business segment, and the

convenience segment. Tailoring its marketing efforts differentially to those

segments made the company’s programs far more effective.(n11)

Conditions Necessary for Customer Tiers: An Empirical Example

In our view, four conditions are necessary for customer tiers to be used

in a company.

• Tiers have different and identifiable profiles.

Profitability differences in customer tiers are most useful when other

variables can identify the tiers. As with customer segmentation, it is

necessary to find ways in which customers vary across tiers, especially in

terms of demographic characteristics. These descriptions can help understand

the tier’s customers and identify appropriate marketing activities.

• Customers in different tiers view service quality

differently. Customers in different tiers can also have different needs, wants,

perceptions, and experiences. Understanding the factors that affect the

customer’s decision to purchase a new product or service from an existing

provider as well as the factors that affect the decision to increase the volume

of purchases from an existing provider are crucial for managing customers for

profitability. If customers in different tiers have different expectations or

perceptions of service quality, these differences will allow the company to

offer different groups of attributes to the tiers.

• Different factors drive incidence and volume of new

business across tiers. Differences in characteristics, needs, wants, and

definition of service quality are likely to result in different drivers for the

incidence and volume of new business. If this condition is met, a company can

target customers that are likely to end up in higher tiers.

• The profitability impact of improving service

quality varies greatly in different customer tiers. Just as direct marketers

routinely qualify lists to test for potential profitability, companies need to

qualify their customer tiers for potential profitability. If customer tiers are

appropriate, the way customers respond to service and marketing should differ

among tiers. Higher tiers should produce a much higher response to improvements

in service quality that will be evident in increases in new business, volume of

business and average profit per customer. Taken together, the

disproportionately greater response to changes in service quality in each of

these areas will result in an overall greater return on service quality

improvements for the higher tiers of customers.

An Empirical Test of the Conditions in a Two-Tier Situation

Virtually all firms are aware at some level that their customers differ

in profitability, in particular that a minority of their customers accounts for

the highest proportion of sales or profit. This has often been called the

“80/20 rule”–twenty percent of customers produce eighty percent of sales

or value to the company. We recently conducted an empirical study to examine

this simple “80-20” scheme.

A major U.S. bank provided profitability information about retail

products and customer information files with descriptive information including

average account balance, average profit from account, and average age, gender,

and income. Data on a random sample of 796 of these customers were merged with

responses to a service quality survey from the same set of customers. Eight

months later, information regarding the amount of new business, including both

the incidence and volume of new business (revenue from new accounts), was added

to the data file by examining behavior following the survey. In this way,

service quality measures could be used to predict future behavior using a

cross-sectional, time-series approach.

Demographic Differences

We examined differences in customer descriptive statistics, service

quality perceptions, drivers of incidence of new business, and drivers of

volume of new business across tiers using various statistical analyses.(n12) We

also projected both the increase in the percentage of customers who would open

a new account and the increase in the average account balance. Multiplying the

projected average account balance by the average profit per account balance for

each tier yielded an estimate for the projected increase in average profit per

account. Multiplying that by the number of accounts yielded the total projected

new profits from each tier.

We then divided the customer base into two customer tiers: the most

profitable 20% (top 20%) and the least profitable 80% (lowest 20%). The results

met all the conditions described above. First, customers in different

profitability tiers had different customer characteristics. The top tier had a

higher percentage of women than the lower tier, an average account balance

about five times as big, and average profit about 18 times as much. The top 20%

was also older than the lowest 20%, had more upper-income customers, and had

far fewer lower-income customers. The top 20% produced more profit per volume

of business, with an average profit per account balance of 2.53%, versus 0.71%

for the lowest 20%. Finally, the top 20% produced 82% of the bank’s retail

profits, an almost perfect confirmation of the 80/20 rule in this profit

setting.

Views of Service Quality

Second, customers in different tiers viewed quality differently. The top

20% viewed service quality in terms of three factors: attitude, reliability,

and speed. By contrast, the lower 20% had a less sophisticated view of service

quality, viewing service as only two factors, attitude and speed, with slightly

different interpretations of the factors. The reliability factor was not a

driver for the lowest 20%. A particularly compelling finding emerged from these

data. When we combined all customers into a single group, all appear to want

the same factors and the factors meant the same thing to both groups. The

important insight here is that blending customer tiers resulted in an imprecise

view of what service quality meant to the customer base.

Drivers of Incidence and Volume of New Business

Third, we found that different tiers had different drivers of incidence

and volume of new business. Since we measured what customers did after they

reported what was important to them, we captured what actually drove customers

to make purchases, rather than what they thought would make them do so. For the

top 20%, speed was key to driving incidence of new business whereas attitude

was the key driver for the lower tier. As before, analyzing the entire customer

base as a single group would have been misleading. Both the combined attitude/

reliability factor and the speed factor were key drivers for the group as a

whole, but the combined analysis would not reveal the fact that different

strategies should be used for different profitability levels.

Profitability Impact

Finally, the profitability impact of improving service quality varied

greatly in different customer tiers. An across-the-board service quality

improvement of the key drivers (approximated by a 0.1 increase in average

satisfaction with each driver in each tier) resulted in a projected 3.65%

increase in incidence of new accounts in the top 20%, but only a 2.00% increase

in the Lower tier. This result suggests that the Top 20% was almost twice as

responsive to the changes in service quality than the lowest 20%. When

examining the projected increase in average account balance, the results were

even more encouraging. The projected increase in average account balance was

$6.19 in the top 20%, but a meager $0.69 in the Lower tier. Here, the Top 20%

appeared to be almost 10 times as responsive to changes in service quality.

Finally, the projected increase in average profit per customer was 15.7 cents

in the top 20%, but 0.5 cents in the lowest 20%. Again, the top 20% provided a

substantially greater return on the service quality improvement. Of particular

interest was that simultaneous improvement of the key drivers for both tiers

produced a projected 89% of the new profits in the top 20%, while only 11% of

the new profits could be attributed to the lower 20%. This was an even higher

percentage than the current percentage.

The Need for More Tiers

The “80/20” two-tier scheme that many companies use assumes

that consumers within each of the two tiers are similar to each other. We

contend, however, that this “best” and “rest” customer

division is rarely sufficient. Just as we showed above the dangers in combining

data from two tiers–the results were muddied and the average did not represent

either tier well–we contend that the lack of distinction among the

“rest” of the levels misses important differences in consumers.

In the two-tier analysis we conducted and in the strategies of companies

that distinguish only between two groups, the customers in the large lower tier

are indistinguishable from each other. This likely masks differences in

demographics, perceptions and expectations of service quality, drivers of new

business, and the profitability impact of improving service quality.

Specifically, if we had observed the demographic differences across four tiers,

rather than two, we would most likely have seen that the lower the tier, the

younger the customer and the lower the average account balance. Many banks

realize that their least profitable customers are students who have no income

and are expensive to serve because they bounce checks and require extra

handling. In the two-tier scheme above, however, this group was not explicitly

articulated and we therefore cannot tell the difference between them and the

rest of the 80%.

Furthermore, in our example we cannot tell whether this lowest-tier

group views quality differently. Banks are coming to understand that

convenience is the critical factor drawing the youngest customers to banks.

Fortunately, a bank that knows this need focus only on that element of quality

with that segment, thereby reducing costs that would be spent if they were

grouped into the rest of the 80% who also wanted the attitude factor. We might

also have observed differences in drivers and incidence of new business,

and–most importantly–in the profit impact of investing in different tiers.

Most companies realize that their customer set is heterogeneous but

possess neither the data nor the analytic capabilities to distinguish the

differences. We suggest that it is highly worthwhile to do so, and to

distinguish more than just the traditional two levels of customers.

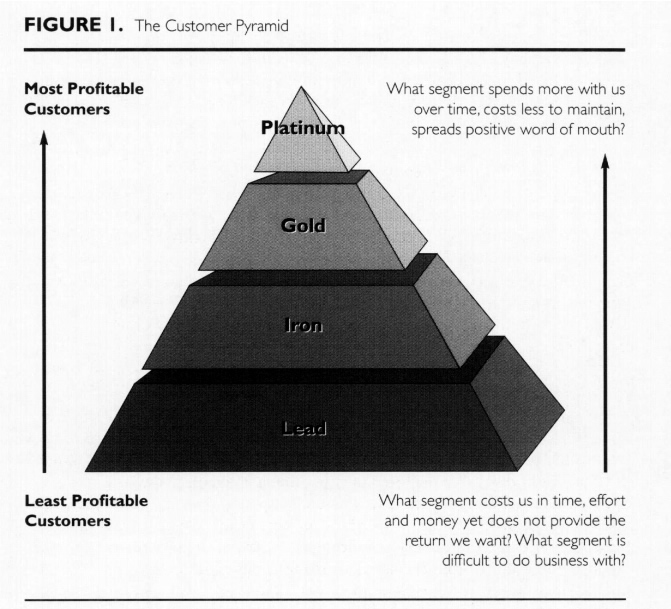

The Customer Pyramid

Large databases and better analytics are likely to reveal greater

distinction among the tiers. Once a system has been established for

categorizing customers, the multiple levels can be identified, motivated,

served, and expected to deliver differential levels of profit. In this section,

we illustrate a framework called the Customer Pyramid (see Figure 1) that

contains (for purposes of illustration) four levels. While different systems

and labels can be useful, our framework includes the following four tiers.

• The Platinum Tier describes the company’s most

profitable customers, typically those who are heavy users of the product, not

overly price sensitive, willing to invest in and try new offerings, and are

committed to the firm.

• The Gold Tier differs from the Platinum Tier in

that profitability levels are not as high, perhaps because the customers want

price discounts that limit margins. They might not be as loyal to the firm even

though they are heavy users in the product category–they might minimize risk

by working with multiple vendors rather than just the focal company.

• The Iron Tier contains customers that provide the

volume needed to utilize the firm’s capacity but whose spending levels,

loyalty, and profitability are not substantial enough for special treatment.

• The Lead Tier consists of customers that are

costing the company money. They demand more attention than they are due given

their spending and profitability, and they are sometimes problem

customers–complaining about the firm to others and tying up the firm’s

resources.

Note that this classification is very different from usage segmentation

done by airlines such as American Airlines because it is based on numerous

variables other than sales that are responsible for profitability of the tiers.

The specific factors vary across industries, but the Customer Pyramid is a rich

and robust concept across most industries and categories. For example, it can

be used successfully by companies selling directly to consumers, to

intermediaries (such as retail, wholesale and professional channels of

distribution), and to other businesses.

Platinum through Lead in the Retail Real Estate Industry

A top-twenty real estate and relocation franchiser has identified the

variables that account for profitability in the retail housing market. In

addition to the cost of the home (for which the franchiser and the broker share

a 6% commission), other variables include:

• the amount of time it takes to buy/sell a home

(which represents the opportunity cost of time and other commissions to the

realtor);

• marketing costs (brochures, open houses,

advertisements);

• customer motivation to purchase/sell (especially

high with relocations);

• price sensitivity of buyers, which may lead them to

negotiate a lower rate with the realtor;

• likelihood of repurchase; and

• referral potential.

Based on these factors, the company defined its Platinum customers as

those who: pay full commission on a home costing $500,000 or more; are

motivated to purchase within the next six months; have purchased more than two

homes in the past; and are members of social or professional networks that make

them candidates to refer other high-end buyers. Gold customers purchase homes

in the $250,000-$600,000 range but are more price sensitive than the top tier.

For example, some Gold customers want to negotiate on the commission or have

the realtors pay points at closing. Notice that some of these customers buy

homes that are in the same price range as Platinum customers but their price

sensitivity reduces their profitability. Gold customers are likely to refer

others, but the types of customers to be referred will are not as valuable to

the firm as those the Platinum customers refer.

Iron customers buy homes in the $100,000-$250,000 range, and include

retirees, young professionals, and families. The company knows that the young

professionals have higher lifetime value potential and therefore market to them

differently than they market to others in this group, who are likely to stay in

the homes they buy. In fact, young professionals who purchase homes at the

upper end are tagged as potential Gold customers and moved to that category

approximately five years after the purchase of a home (U.S. consumers move, on

average, every five years). Many Iron customers are relocations from other areas

and are pressed to buy homes quickly, making them good prospects for the

company despite home prices that are lower than the top two tiers. Lead

customers are high maintenance customers who are shoppers rather than buyers.

Some Lead customers spend as long as two years looking at homes, calling upon

realtors to show them homes when they have free time (many realtors complain

about the “my-husband-is-watching-football” Saturday shopper, who is

merely looking to be entertained rather than to buy). While they might be

looking at homes in all price ranges, the homes they buy are likely to be under

$100,000. These clients are often dissatisfied with what they see, making them

less likely than other tiers to send qualified referrals to the company.

While the real estate company is still refining the criteria for the

tiers. They view the sorting into levels as invaluable in qualifying current

and potential clients, and are developing different programs for reaching and

serving them differentially. They have recently developed an “expectations

assessment tool” that attempts to decide the appropriate customer tier

upon making the contract with the buyer or seller.

Differentiating Business Customers in the Marketing Research Industry

One of the most respected marketing research firms in the country

learned in the mid-nineties that it didn’t pay to treat all clients alike. In

addition to absolute dollar amount clients spent, they could be differentiated

on a number of other factors, notably the willingness to be a research partner

and commit to an annual budget. Firms that were willing to do so required very

low selling costs while firms that bought research on a project-by-project

basis required selling costs as high as 25% of the sales dollars they brought

in.

Platinum customers for this firm were defined as large accounts that

were willing to plan a certain amount of research during the year. The timing

and nature of this research could be anticipated, making it easy for the

research firm to smooth supply and demand. The Platinum clients tended to stay

with the company and were willing to try new services and approaches developed

by the research firm. Therefore, they bought across research service types

(e.g., field and tab services, statistical studies, exploratory studies) and

had minimal sales costs averaging only 2-5%. Best of all, they were willing to

serve as references for the firm, allowing the firm to give their names to new

clients wanting recommendations about the company. They were loyal to the firm

and used other marketing research companies only when they needed something the

firm could not provide.

Gold customers had similar profiles except that they were more price

sensitive, inclined to spread their research budgets across several firms.

While they were large accounts and had been customers for multiple years, they

were not willing to plan for a year in advance even though the marketing

research firm would give them better quality if they did. They provided

referrals but on an ad hoc basis.

Iron customers were moderate spenders and conducted research on a

project basis, sending out requests-for-proposals whenever they were conducting

studies. They were looking for the lowest price and often did not allow

sufficient time to perform the jobs. Because they had no overall plan, projects

came in at any time, sometimes in the off season (which helped the firm use

their capacity) but sometimes during peak season (which created difficulties in

allowing the firm to service its best customers well). Selling costs were high

because the firm continually kept in personal and mail contact hoping to move

these Iron customers up the Pyramid.

Lead customers spent little on research, conducted isolated projects

that were usually of a “quick and dirty” nature. Selling costs were

highest in this group, for most advertising and almost all speculative

presentations were targeted to these accounts and salespeople had to spend

multiple visits to get them. Furthermore, once they became clients, Lead

customers were “high maintenance” clients that cost the firm money

because they didn’t understand the process of research. They often changed

projects mid-stream and expected the firm to absorb the costs.

Recognizing the Differences among Doctors

Pharmaceutical companies depend on doctors to prescribe their branded

drugs over competitive or generic drugs. Rarely do end consumers make these

decisions for themselves. Faced with environmental threats such as HMOs,

hospital purchasing alliances, and pharmacy consortiums–all of which lowered

pharmaceutical profits–a major pharmaceutical firm strove to reduce its costs

and improve the efficiency of its marketing. The first step it took was to

recognize through careful analysis that all doctors were not equally profitable

customers. The company departed from industry practice and began to view

physicians as long-term strategic assets and thereafter targeted them based on

potential profitability across the company’s drug portfolio (rather than on

current sales within a single therapeutic category). In addition to the

cross-product focus, the firm also was able to calculate with some degree of

accuracy the selling costs per physician (e.g., $125 for a call from a sales

representative, $25 for product samples, $5 for share of advertising materials).

The key inputs to their analysis were:

• the volume of prescriptions a particular physician

generated (measured by data from a source called Walsh America, which captures

physician-level prescribing data at the retail pharmacy level);

• value of a prescription (from a source called IMS

Americas);

• cost of a sales call;

• cost of product samples;

• product gross margins, rebates, and discounts.

Market growth rates and share forecasts were provided by the marketing

department. Two other variables perceived by salespeople were also factored

in–the physician’s capability of having an impact on a territory through word

of mouth communication, and the physician’s perceived responsiveness to sales

efforts. Potential profit calculations were made for all physicians, and then

these calculations were used to sort the doctors into tiers.

The top tier consisted of the doctors most likely to give the greatest

return on the company’s sales investment. Contribution margins for the

physicians were highest in this group and costs were low enough that profits

exceeded that of the other groups. Importantly, these were physicians who were

willing to see sales representatives (and thus were “sales

sensitive”). Only 10% of the physicians fell into this top tier. The Gold

physicians were high-profit physicians that were relatively inaccessible,

either because they were unresponsive to sales efforts, at the end of their

careers (hence their potential was not as high) or lived in geographically

distant areas. While this group accounted for almost 35% of physicians, the

company did not allocate salespeople to them because of the low payback;

instead, they handled this group through marketing efforts using the telephone

or mail. Because the marketing approaches were less expensive than personal

selling, the profit margins were sometimes close to those of Platinum doctors

although the sales volumes were lower. Doctors in the Platinum and Gold level

tended to be the influencers/opinion leaders among their peers.

The Iron doctors were new physicians that were vital to the future of

the company. Typically, they were evaluated as such based on judgments of their

sales representatives. If the representatives thought the doctors had potential

to influence others or would be responsive to sales efforts, they were

classified as Iron. If not, they were classified as Lead. Sales managers

reviewed the classification of the two lower groups on an annual basis to

assure that salespeople were accurate in their assessments.

The company’s efforts to target physicians paid off quickly. Salespeople

from territories high in Platinum doctors tended to have bonuses 10-25% higher

than average, while those from territories heavy with Lead customers received

bonuses 4-7% below average. Prior to the targeting, the bonus spread was

significantly smaller–than 2-5% higher in Platinum and less than 1% below

average in the Lead group.

When Should a Firm Use the Customer Pyramid?

From the firm’s point of view, the Customer Pyramid is desirable

whenever the company has customers that differ in profitability but is

delivering the same levels of service to all customers. In these situations,

the firm is using limited resources to stretch across a wide group of

customers, possibly under-serving its best customers. In each of the following

conditions, it makes financial and practical sense to implement the Customer

Pyramid approach.

• When service resources, including employee time,

are limited. One of the most important reasons for ascribing to the Customer

Pyramid is to prevent the undesirable situation in which a company’s best

customers do not obtain the service they require because the company is

expending too much time and effort on its least profitable customers. A

restaurant would not want to fill up all its tables with students purchasing

coffee with endless refills when customers who purchase soup-to-dessert dinners

are kept waiting. Whenever any resource, such as employee time, is limited, a

firm must identify the best use of the limited resource. This situation occurs

frequently in professional services such as consulting, accounting,

advertising, and architectural design. A firm has only so much professional

time available and its allocation must be done carefully so that the best

customers are not kept waiting for their jobs while smaller and less profitable

customers are served.

• When customers want different services or service

levels. In many industries, particularly those with high technology or

information technology offerings, customers have divergent requirements and

aptitudes for service. One telephone company, for example, viewed its business

customers as being comprised of three groups: sophisticated CIOs who wanted to

configure their own systems and needed minimal service assistance from the

vendor; middle managers of large firms who wanted to purchase complex systems

but needed considerable consulting to develop the best configuration; and CEOs

of small firms who wanted sturdy, competent systems that were easy to

understand and that included basic maintenance service. The three decision

makers had completely different requirements; treating them with the same

levels of service at the same high price would not only be inefficient, but

ineffective as well. Serving these different customers involves widely

different costs that are wasted if all customers are treated the same way.

• When customers are willing to pay for different

levels of service. Package delivery services such as Federal Express charge

varying rates based on the type of delivery and the speed with which a package

is delivered. The different types of delivery include express package service

(under 150 pounds), express freight service (over 150 pounds), FedEx Letter,

FedEx Pak, FedEx Box, and FedEx Tube, all of which have different prices

associated with them. Speeds of delivery include FedEx Priority Overnight,

FedEx Standard Overnight, and FedEx 2-day, each with different prices. A

customer can also purchase Saturday delivery and special handling–as

expected–at additional cost. Customer sensitivity to these different services

is high, leading to a willingness to pay considerably more or less depending on

the desired delivery and speed.

• When customers define value in different ways.

Customers define value in one of four ways: value is low price; value is

whatever a customer wants in a product or service; value is quality divided by

price; and value is all that a customer gets for all that he or she gives.(n13)

In addition to monetary price, customers also consider non-monetary prices such

as time, effort, convenience, or psychic costs. When a service company has

customers with all of these definitions of value, tiers of service can be

designed to capture the best financial returns for the company depending on

what the customer expects in terms of value. Perhaps the first value definition

(value is low price) would cover the company’s lowest level or Lead customers;

this segment would be willing to accept less in exchange for paying less.

Customers with the second value definition (value is whatever I want in a

product or service) might be Platinum customers because they are not price

sensitive. If their needs mesh with high-margin services the firm can provide,

both buyer’s and seller’s needs are met. In between these two levels fall the

Gold and Iron segments with value definitions that are both service- and

price-sensitive, leading them to be more profitable than the Lead tier but less

profitable than the Platinum tier.

• When customers can be separated from each other.

Firms are and should be sensitive to the fact that customers in the lower tiers

of the pyramid will be angry if they see other customers receiving better

treatment than they receive. Unless the reason is readily apparent for service

differentials (such as a 15% discount for seniors at a restaurant), the

customers in different categories should not know that those in other tiers are

viewed as different or are receiving different levels of service. As an

example, telephone companies such as AT&T now have state-of-the-art

customer service centers that can immediately identify which tier customers fit

in when their call comes in to the customer service center. These automatic

systems immediately route customer calls to different centers based on the

value of the customer to the company. Once there, service standards such as

length of time spent on a customer call differ depending on the tier of

customer.

• When service differentials can lead to upgrading

customers to another level. On the other hand, there are substantial benefits

in some services for customers clearly seeing what other customers receive. For

example, main cabin airline customers note that the services in the first-class

cabin are better than what they receive but the difference is substantiated by

the obvious fact that those customers paid more for their seats. Another reason

why customers are in first class is that they receive complimentary upgrades

for being frequent travelers. Armed with this knowledge, otherwise non-loyal

airline travelers may be motivated to consolidate their airline trips on a

specific airline to be able to take advantage of these benefits.

• When they can be accessed either as a group or

individually. The traditional marketing strategies of product, price,

promotion, and place need to be adapted for the different tiers. Instead of

viewing the market as a uniform group of customers with similar potential, the

firm needs to view them as distinct groups with differing potential. At its

best, this means developing different marketing strategies for each tier,

especially different strategies for price and offering. To do so, the firm must

be able to access the customers selectively.

Customer Alchemy

Customer alchemy is the art of turning less profitable customers into

more profitable customers. It can take place at any tier along the Customer

Pyramid, but is more difficult at some levels than at others. For example, it

is very difficult to move Lead customers up to Gold or Platinum tiers, and it

is often necessary to “get the Lead out” rather than try to move

those customers up. If the decision is made to keep Lead customers, the

strategies used are typically different than those used at other tiers.

Turning Gold into Platinum

The most important requirement for turning Gold customers into Platinum

customers is to fully understand them and their individual needs. With an

industrial or business-to-business firm and a dedicated sales force, this need

is often met because the salesperson knows the business well enough to stay

constantly in touch with the client and to anticipate his or her needs. This

customer intimacy, when effective, allows the company to move the customer to a

higher tier because the firm can develop offerings that satisfy the client’s

needs, identify existing ways to serve the client better, and communicate in

the right way at the right times to clients.

When a company has a larger number of customers, the process of turning

Gold into Platinum may seem more daunting but still involves the same basic

foundation: building information profiles of customers that form the basis for

becoming a full-service provider of whatever the firm can offer. Building these

profiles may involve collecting and consolidating existing information about

the customer’s history with the firm, including usage and customer satisfaction

information. Alternatively, profiles may involve conducting very individualized

customer research such as personal interviews or customer expectation sessions.

Only when company fully understands its Gold customers can it design strategies

to turn them into Platinum customers.

The following strategies are recommended for turning Gold customers into

Platinum customers.

Become a Full-Service Provider

Home Depot, the U.S. hardware giant, has a strategy for making its good

(Gold) customers into great (Platinum) customers. The highly successful

hardware superstore, which sells to virtually all levels in the Customer

Pyramid, has a new strategy for two groups of high potential

customers–traditional customers who want to make major home renovations and

housing professionals such as managers of apartment and condominium complexes

and hotel chains. Together, these groups spend about $216 billion every year

and Home Depot wants customers to spend all of it in its stores by becoming a

full-service provider, offering everything these customers could possibly need

to do their jobs.

The cornerstone of its strategy is the creation of Expo Design Centers.

The design centers not only show off the expanded line of physical products the

company offers but configure the products into finished and polished showrooms.

Rather than just having row upon row of nails, hammers, and tile, the store is

creating a showplace for upscale renovation, including complete kitchens with

state-of-the-art appliances, finished baths, and antiques.(n14) Expo is a

one-stop-shopping location for major renovations, which usually require

homeowners to assemble a group of contractors and designers, then make separate

trips to buy tiles, materials, drapes, appliances, and the like. All of these

are now available at an Expo, making it unnecessary for a member of their

target segments to buy from any other store to do their renovations.

Industry-certified designers and project managers oversee the entire project from

beginning to end, making even general contractors expendable. With this

strategy, Gold customers become Platinum customers, getting everything they

want from their full-service supplier, Home Depot.

Provide Outsourcing

One of the best examples of moving customers from Gold to Platinum

levels involves outsourcing, taking on an entire function that a customer firm

used to perform for itself and providing it for them. From payroll and

accounting to personnel and even strategy,(n15) outsourcing firms are doing for

their clients what is either too costly or specialized for them to do

themselves. In these situations, the nonmonetary costs to the client firms of

engaging in these activities reduce their ability to perform their core

competencies. The effort involved, for example, in staying abreast of new

information technology, maintaining systems, fixing hardware and software

problems, and keeping qualified staff all become an interference with the

firm’s true purpose. In these and other cases of outsourcing, a supplier firm

can perform these functions for a customer, thereby tying the customer to the

organization and making the customer’s business predictable, increasing their

value to the company.

Increase Brand Impact by Line Extensions

Women’s clothing is an area where few companies “own”

customers in the sense that customers buy predominantly one brand and would

therefore be considered “Platinum” customers. Liz Claiborne, the

world’s largest women’s apparel maker and marketer, however, has changed this

customer behavior in its key segments. The company bonded with the female baby

boom generation, being one the first companies to target them and truly

understand them and their needs. Recognizing that baby boomers were a

physically fit generation that didn’t want to appear to age, the company

created clothing that allowed customers to continue to appear slim despite a

few added pounds. It convinced its target group that it really knew them,

thereby establishing a fit with them both literally and emotionally. Then the

company very successfully extended its product lines: Liz Collection for

professional clothing, Liz Wear for casual clothes, Elizabeth for large women,

Dana Buchman for women who can afford designer clothing. The company was so

successful in its strategy that it extended its lines into pocketbooks, shoes,

belts, jewelry, and even perfume.

Create Structural Bonds

Structural bonds (or learning relationships) are created by providing

services to the client that are frequently designed right into the service

delivery system for that client. Often structural bonds are created by

providing customized services to the client that are technology-based and serve

to make the client more productive. Allegiance Healthcare Corporation, a

spin-off of Baxter Healthcare, provides an example of structural bonds in a

business-to-business context. The company has developed ways to improve

hospital supply ordering, delivery, and billing that have greatly enhanced

their value as a supplier. They created “hospital-specific pallet

architecture” that means that all items arriving at a particular hospital

are shrink-wrapped with labels visible for easy identification. Separate

pallets are assembled to reflect the individual hospital’s storage system, so

that instead of miscellaneous supplies arriving in boxes sorted at the

convenience of Allegiance’s needs (the typical approach used by other hospital

suppliers), they arrive on “client-friendly” pallets designed to suit

the distribution needs of the individual hospital. By linking the hospital

through its ValueLink service into a database ordering system, and providing

enhanced value in the actual delivery, Allegiance has structurally tied itself

to its over 150 acute-care hospitals in the United States. In addition to the

enhanced service ValueLink provides, Allegiance estimates that the system saves

its customers an average of $500,000 or more each year.(n16)

An excellent example of structural bonds in business-to-consumer markets

is Hallmark’s Gold Crown Card program that identifies what each customer values

about his or her relationship with Hallmark as a platform for turning him or

her into a Platinum customer. After enrolling at any Hallmark store, customers

are immediately mailed high-quality plastic cards that can be used within a

month to earn bonus points. Thereafter, for every dollar spent and for every

Hallmark card purchased they earn points that accumulate and turn into dollar

savings. At 300 points per quarter, a customer joins the equivalent of a Gold

tier, receiving a personalized point statement, a newsletter, Reward

Certificate, and individualized news of new products and events at local

stores.

In 1996, Hallmark created its Platinum level for the very top 10% of

customers who buy more cards and ornaments than others. They are sent elaborate

mailing pieces with gold seals and new membership cards clearly identifying

them as preferred members. Along with amenities (such as longer bonus periods

and their own private priority toll-free number), the company communicates with

them individually about the specific products they care about. Buyers of

Christmas Keepsake ornaments receive specialized information about them,

whereas heavy buyers of cards receive free cards to introduce new lines.

Because these communications are not programmed, customers experience surprise

and delight.(n17)

Results have been impressive. In addition to over 50 consecutive months

of share gains since inception of the program, the revenue represented by Gold

Crown Program (in our terminology Platinum) members was more than a billion

dollars in 1997 and over $1.5 billion in 1998. Member sales represent 35

percent of total store transactions and 45 percent of total store sales.(n18)

Offer Service Guarantees

Because service problems and dissatisfaction lead to customer

defections, companies must use the most powerful methods to find out when

service problems occur and then to resolve them quickly and completely.

Possibly the most effective strategy for accomplishing this is the service

guarantee, whereby a company assures customers that they will be satisfied or

else they receive some form of compensation commensurate with their problem.

While many forms of service guarantees exist, and cover different aspects of

service (meeting deadlines, delivering a smile, achieving reliability), the

type of service guarantee most relevant for the very best customers is a

complete satisfaction guarantee. This can take several forms, but the form that

is best for the customer assures satisfaction and, lacking satisfaction,

promises the customer that any problems that occur will be fixed immediately.

Strategies exist for effective guarantees–they should, for example, be easy to

invoke and have a clear payoff–and these should be followed to create the very

best guarantee possible. That way, Gold customers will have no reason to leave

and will want to stay and become Platinum customers.

Turning Iron into Gold

Customer alchemy can also change something ordinary (a less profitable

Iron customer) into something valuable (a more profitable Gold customer). There

are many ways to turn Iron customers into Gold customers. The foundation

involves finding out what is most important to the Iron customers–not assuming

that it is the same thing that is important to Gold customers–and then

attending to the specific factors that drive the Iron customers’ satisfaction

and behavior. With this lower level of customers, it is rarely necessary to

find out what makes each individual customer satisfied. Instead, it is critical

to find the key drivers of the relationships across the customers in the tiers.

In our example, we saw how improving the key driver of the lower 80% (attitude)

could increase both incidence of new business and volume of new business,

thereby turning some lower-tier customers into upper-tier customers. Once we

identify these factors, we can use one of the following strategies to increase

usage and profitability of those customers.

Reduce the Customer’s Nonmonetary Costs of Doing Business

Since the idea in the Customer Pyramid is not to reduce price and

thereby lower profit margins, a company should constantly be looking for ways

to lower the nonmonetary costs of doing business with customers. An excellent

approach to this strategy involves reducing the hassle and search costs that

customers associate with making purchases in many high-technology categories

today. Small businesses, for example, have tremendous difficulty deciding what

forms of communication technology to buy and from which suppliers. So many offerings

and combinations of offerings exist and a plethora of providers constantly

besiege customers with differences that are difficult for them to discern.

Alltel, a full-service high-technology communications firm, offers an answer

that works very well for small businesses and individuals. A customer can

obtain all three components–paging, wireless, and long distance–from the

company, have it all appear on the same bill, and deal with all service

problems easily by having only one customer service department for all three

services. In doing so, the company has also increased its business with the

customer, as it now obtains not just the customer’s paging business or long

distance business or wireless business, but all three. The costs of dealing

with the customer are reduced as well, because handling a single customer with

three services costs less internally than handling three different customers,

each with a single service. The customer is now a Gold customer rather than an

Iron customer and is far more strongly linked into the firm because its

associations cross service categories.

Add Meaningful Brand Names

One of the most effective strategies some discount retailers have used

recently to turn Iron customers into more profitable Gold customers is to create

a brand-within-a-brand image in their stores. Typically, this involves

associating product lines in the stores with more favorable brand images than

those of the store itself. For example, when K-mart was working to improve its

image and profitability, it affiliated with Martha Stewart to manufacture and

market an entire line of household soft goods such as sheets and towels. The

line carried Martha Stewart’s name and was priced considerably higher than

other goods in the same category in K-mart. Rather than making small profit

margins on these items, the company began to make much larger margins. It also

generated loyalty and multiple purchases because the line of products was

color-coordinated. Customers wanted to buy these products not because they were

associated with K-mart but because they were affiliated with a very favorable

and well-known person. By associating with this favorable brand, the store

created a brand personality where none existed in the past and was able to

improve the profitability of that product category in the store. As it became

clear that the branding was successful, the company extended it beyond its

original bounds to include other products.

Become a Customer Expert through Technology

One of the best examples of turning Iron customers into Gold customers

involves the battery of strategies used by Amazon.com, the online bookstore.

Initially, the company focused on being able to get virtually any book that the

customer wanted. Once it established this ability, it recognized that

developing profiles of individual customers was a winning strategy. Once a

customer had purchased something from Amazon.com, the company started to build

its information database about the customers’ preferences. Whenever a customer

ordered a book, the database produced a list of books from the same author and

on similar topics that could expand the purchase. These suggestions were often

very welcome to the customer, who might not have been aware of the other books.

After multiple purchases, the database was designed to make suggestions as soon

as the customer signed on, again increasing purchases. Before long, the company

discovered that customers who bought books also bought CDs and movies, and it

expanded its product lines to satisfy these other needs of its customers. To

top the strategy off, the company asked customers if they wanted to receive

information about products that were new and dealt with their interests. Using

the customer’s e-mail address, Amazon.com thereby created ongoing communication

with customers about their personal interests, making it so easy to deal with

the company that customers began spending all their book dollars–as well as CD

and movie dollars–at Amazon.

Become a Customer Expert by Leveraging Intermediaries

Caterpillar, the world’s largest manufacturer of mining, construction,

and agriculture heavy equipment, owes part of its superiority and success to

its strong dealer network and product support services offered throughout the

world. Knowledge of its local markets and close relationships with customers

built up by Caterpillar’s dealers are invaluable. “Our dealers tend to be

prominent business leaders in their service territories who are deeply involved

in community activities and who are committed to living in the area. Their

reputations and long-term relationships are important because selling our

products is a personal business.”(n19)

Develop Frequency Programs

Most retail firms can benefit from frequency programs that encourage

customers to spend more with the company in order to receive special benefits.

Convenience-item retailers like VCR rental companies can effectively use

frequency programs. Blockbuster, for example, developed a program called

Blockbuster Rewards. For a one-time payment of $9.95, a customer is able to get

benefits that include: rent five videos, get one free every month; two free

video rentals a month just for joining; and one free video rental with each

paid movie or game rental every Monday through Wednesday. Notice that it is not

the one-time fee that makes the Blockbuster Rewards customer a Gold

customer–it is the frequent use of the service. The firm is motivating the use

of capacity that it cannot otherwise sell, and encourages customers to turn to

Blockbuster for all their video rental needs. Blockbuster did not drop the

price on its video rentals, which would lower its profits. In fact, the company

increased prices and reduced the number of days a new video could be rented

from two to one.

Create Strong Service Recovery Programs

A strong service recovery system–one that catches all possible service

errors and corrects them promptly and appropriately–is critical to turning

Iron into Gold. The best recovery systems proactively identify when customers

who make purchases are let down by a company’s product or an interaction with

someone from the company. A company must have processes in place to rectify

these situations, whether they involve billing, delivery, or any other

company-customer interface.

Getting the Lead Out

Allocating more effort to customers that are more valuable implies

allocating less effort to customers that are less valuable. In particular, Lead

customers weigh the company down. They are the customers who don’t pay their

bills. They are the college students who bounce checks. They are the telephone

customers who run up large long distance bills that require the company to pay

agencies to collect. They are the industrial firms who make purchases and then,

in disputes over deliveries or quality, let their invoices go 60 or 90 days or

longer.

Lead customers are also those who buy so little that dealing with them

costs more than they are worth. Marketing and personal selling expenses may

exceed the profit on small business accounts. Transaction costs for customers

who place orders for one or two items in a year make them unprofitable. As is

sometimes the case, the smallest customers also expect the most in terms of

service, making the cost of handling them far higher than the profits received

from them.

Attempting to move customers from Lead to higher categories is not an

easy task, and it is not always recommended. Only if the future potential of a

Lead customer is known to be high (for example, the MBA student who is

currently an unprofitable banking customer) is enduring a period of customer

unprofitability justified. During this time, the firm could attempt to make

these customers more profitable, something that can be accomplished in two

basic ways: prices can be raised or costs to serve the customers can be

reduced.

Raise Prices

One effective approach is to increase prices to Lead customers by

charging for services they have been receiving but not paying for. A software

company that has been giving free technical help to Lead customers (who, by

definition, typically abuse the privilege) can begin to charge for the service.

True Lead customers will leave rather than pay; others may choose to stay and

thereby join the Iron category because of the added revenue they contribute to

the firm.

An excellent example of this strategy is being used by a number of both

large and small telephone companies with customers who don’t pay their bills.

Typically, this segment of customers owes one of the larger companies a

considerable amount of money (greater than $300) in long distance charges and

has not made progress in paying it off. Their phone service has been cancelled

and they no longer can get even local service. Enter companies like E-Z Tel of

Dallas and Annox of Pleasant View, Tennessee, who offer pre-paid local service.

To get the service, a customer has to go to a local pawnshop and plunk down $49

in cash plus $2 for a money order (compared to $17 for a regular customer). The

customer then receives local phone and 911 service for the next month, despite

owing a debt to a long distance company. This niche market, consisting of about

6 million households that go unserved because of unpaid phone bills, offers

considerable profit at these higher prices. The small companies that serve this

market buy service from a local phone company at a 20% discount and resell it

at a 300% premium. To these customers, giving up more in terms of price is not

the issue–having the telephone service is of most value to them. While the

examples we provide here are small independent companies, many large telephone

companies are starting to offer the service to compete in this market because

it is profitable. In most cases, they are changing the brand name that they

sell the service under to avoid undermining their image in other tiers.(n20)

Reduce Costs

The alternative to raising prices among Lead customers is to reduce

costs and find ways to serve the segment more efficiently. Banks have

accomplished this by reducing the number of full-service branches with tellers

and staff and replacing them with ATMs that are able to service customers for

far less money. Many banks have identified the customer group that is on the

bottom tier of the Customer Pyramid as college students. These customers have

very little money of their own, cannot afford savings accounts, and often shop

for and obtain free checking accounts. While banks realize that these customers

may someday be good customers–and therefore do not want to alienate them–they

also recognize that serving them is expensive. They therefore are developing

strategies for dealing with these customers in inexpensive ways. For example,

they encourage the students to bank by telephone, ATM, or the Web, sometimes

going so far as to require a fee if they visit tellers more than two or three

times a month. They require the students to have overdraft checking, a money

maker for banks, to avoid the high cost and inconvenience (to the bank) of

bounced checks. They charge high fees when monthly payments are not on time.

Many business-to-business firms that previously served all customers

with personal salespeople now handle only Platinum or Gold customers that way,

serving Iron and Lead customers with inside salespeople. IBM made a

revolutionary switch from its historical way of dealing with customers when it

realized in the early 1990s that it was highly inefficient to serve all small

customers with the personal service that had characterized the firm in the

past. Rather than have customer engineers personally fix old machines for

unprofitable customers for free, the company started to charge for these

repairs as well as develop ways to fix machines remotely, thereby saving money.

Get the Lead Out

It is very difficult to move most Lead customers from the low tier to a

higher tier because they have characteristics that make them less desirable

customers. They either don’t pay their bills, don’t have much money to spend,

don’t need what the company offers, or don’t have the qualities that make them

loyal to companies. If either or both of the two approaches discussed above are

not effective, then the wisest solution is often for the company to try to free

itself of them. The firm must do this carefully so that customers do not spread

negative word of mouth that could deflect potentially profitable customers from

choosing the firm.

Serving Customers According to Their Tiers

Once the tiers have been established, various elements of service

strategy can be adjusted to the tiers. For example, the need for customer

information varies by tier. With Platinum and Gold customers, it is desirable

to know individually what each customer wants so as to develop a custom profile

of each customer’s history, preferences, usage, and expectations. For Iron

customers, on the other hand, segment preferences and perceptions are usually

adequate. Lead customers may be studied for different purposes altogether, such

as to examine ways that they may be served more efficiently and with less cost.

The most important marketing task implied by the Customer Pyramid is to

serve the most profitable customers in ways that extend and enrich their

relationships with the company. Careful consideration should be given to the

product and service needs of these customers and to their value propositions.

However, if the firm is to maintain profitability among these tiers, it must be

careful not to focus on improving the value proposition mainly by discounting

and other price-related strategies. Lowering prices reduces the profitability

of the segment, often unnecessarily, for price may not be high on the list of

requirements for this segment.

Profit Implications of Moving Customers Up the Pyramid

The use of the Customer Pyramid can supercharge a company’s profits as

it eliminates unprofitable customers and converts lower-tiered customers to

higher-tiered customers using targeted and efficient strategies. A major

automotive manufacturer has used a four-tier Customer Pyramid approach to

identify its dealers’ best customers, their average number of service visits,

and their spending per visit. In one of its major dealerships, the service

revenue differences across these groups (when number of visits and average

amount spent/visit are considered) are striking: $3,743 for Platinum (6,554

customers), $2,713 for Gold (2,609 customers), $620 for Iron (2,720 customers) and

$263 for Lead (19,549 customers). In speaking to the CRM manager at this global

automotive company we have learned that they are still working on the profit

and CLV implications of this analysis, but have not achieved it yet. However,

even examining revenue shifts provides insight into the power of the model. The

implication of moving even 20% of the Lead customers to the Iron category is an

improvement of $697,899 in revenue. Moving 10% of the Iron to Gold improves

revenue by $565,110.

This same manufacturer has also examined the gross profit (at another

dealership) from distinct profit tiers of customers–those customers who have

no service performed at the dealership (Iron), those who have some service

(Gold) and those who have all of their service performed at the dealership

(Platinum). In a comparison of their Gold and Platinum customers, the company

found that Gold customers generate $1674 in gross profit to the dealership,

while Platinum customers generate $2,259. We can see that each Gold customer who

is motivated to have all of his/her service performed at the dealership (moved

to Platinum) results in an additional $585 in gross profit to the dealership.

If we can motivate 10-20% of such customers to change their behavior in this

way, we have the opportunity to increase gross profit by almost $1 million–not

a trivial amount for an automobile dealership. As these real-life examples

illustrate, there is a tangible benefit to understanding what motivates

customers at each tier of the pyramid and to crafting marketing strategies to

motivate customers to move “up the Pyramid.”

Summary

Customer profitability can be increased and managed. By sorting

customers into profitability tiers (a Customer Pyramid), service can be

tailored to achieve even higher profitability levels. Highly profitable

customers can be pampered appropriately, customers of average profitability can

be cultivated to yield higher profitability, and unprofitable customers can be

either made more profitable or weeded out. Tailoring service to the customer’s

profitability level can make a company’s customer base more profitable,

increasing its chances for success in the marketplace.

Notes

(n1.) R. Brooks, “Alienating Customers Isn’t Always a Bad Idea,

Many Firms Discover,” Wall Street Journal, January 7, 1999, pp. A1 and

A12.

(n2.) V. Zeithaml, “Service Quality, Profitability, and the

Economic Worth of Customers,” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science,

28/1 (Winter 2000): 67-85.

(n3.) R. Buzzell and B.Gale, The PIMS Principles: Linking Strategy to

Performance (New York, NY: The Free Press, 1987).

(n4.) Zeithaml, op. cit.

(n5.) R.N. Bolton and J. Drew, “A Longitudinal Analysis of the

Impact of Service Changes on Customer Attitudes,” Journal of Marketing,

55/1 (January 1991): 1-9.

(n6.) R.T. Rust, A.J. Zahorik, and T.L. Keiningham, Return on Quality:

Measuring the Financial Impact of Your Company’s Quest for Quality (Burr Ridge,

IL: Irwin, 1994).

(n7.) V.A. Zeithaml, L.L. Berry, and A. Parasuraman, “The

Behavioral Consequences of Service Quality,” Journal of Marketing, 60/2

(April 1996): 31-46.

(n8.) R.N. Bolton, “A Dynamic Model of the Duration of the

Customer’s Relationship with a Continuous Service Provider: The Role of

Satisfaction,” Marketing Science, 17/1 (Winter 1998): 45-65.

(n9.) A.J. Zahorik and R.T. Rust, “Modeling the Impact of Service

Quality on Profitability: A Review,” in Terri Swartz et al., eds.,

Advances in Services Marketing and Management (Greenwich, CT: JAI Press, 1992),

pp. 247-276.

(n10.) G. Hartfeil, “Bank One Measures Profitability of Customers,

Not Just Products,” Journal of Retail Banking Services, 18/2 (1996):

24-31.

(n11.) D. Connelly, “First Commerce Segments Customers by Behavior,

Enhancing Profitability,” Journal of Retail Banking Services, 19/1 (1997):

23-27.

(n12.) R. Rust, V. Zeithaml, and K. Lemon, Driving Customer Equity: How

Customer Lifetime Value is Reshaping Corporate Strategy (New York, NY: The Free

Press, 2000).

(n13.) V. Zeithaml, “Consumer Perceptions of Price, Quality and

Value: A Means-End Model and Synthesis of Evidence,” Journal of Marketing,

52/3 (July 1988): 2-22.

(n14.) J.S. Johnson, “Home Depot Renovates,” Fortune, November

23, 1998, pp. 200-204+.

(n15.) James Brian Quinn, “Strategic Outsourcing: Leveraging

Knowledge Capabilities,” Sloan Management Review, 40/4 (Summer 1999):

9-22.

(n16.) Robert Hiebeler, Thomas B. Kelly, and Charles Ketteman, Best

Practices: Building Your Business with Customer-Focused Solutions (New York,

NY: Simon and Schuster, 1998), pp. 125-27. Discussed in V. A. Zeithaml and M.

J. Bitner, Services Marketing and Management (New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, 2000).

(n17.) F. Newell, Loyalty.com: Customer Relationship Management in the

New Era of Internet Marketing (New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, 2000), pp. 232-236.

(n18.) Ibid., p. 236.

(n19.) D.V. Fites, “Make Your Dealers Your Partners,” Harvard

Business Review, 74/2 (March/April 1996): 84-95.

(n20.) K. Schill, “Dial-a-Deal,” The News and Observer,

January 31, 1999, p. E1-3.

California Management Review Summer2001, Vol. 43

Issue 4, p118